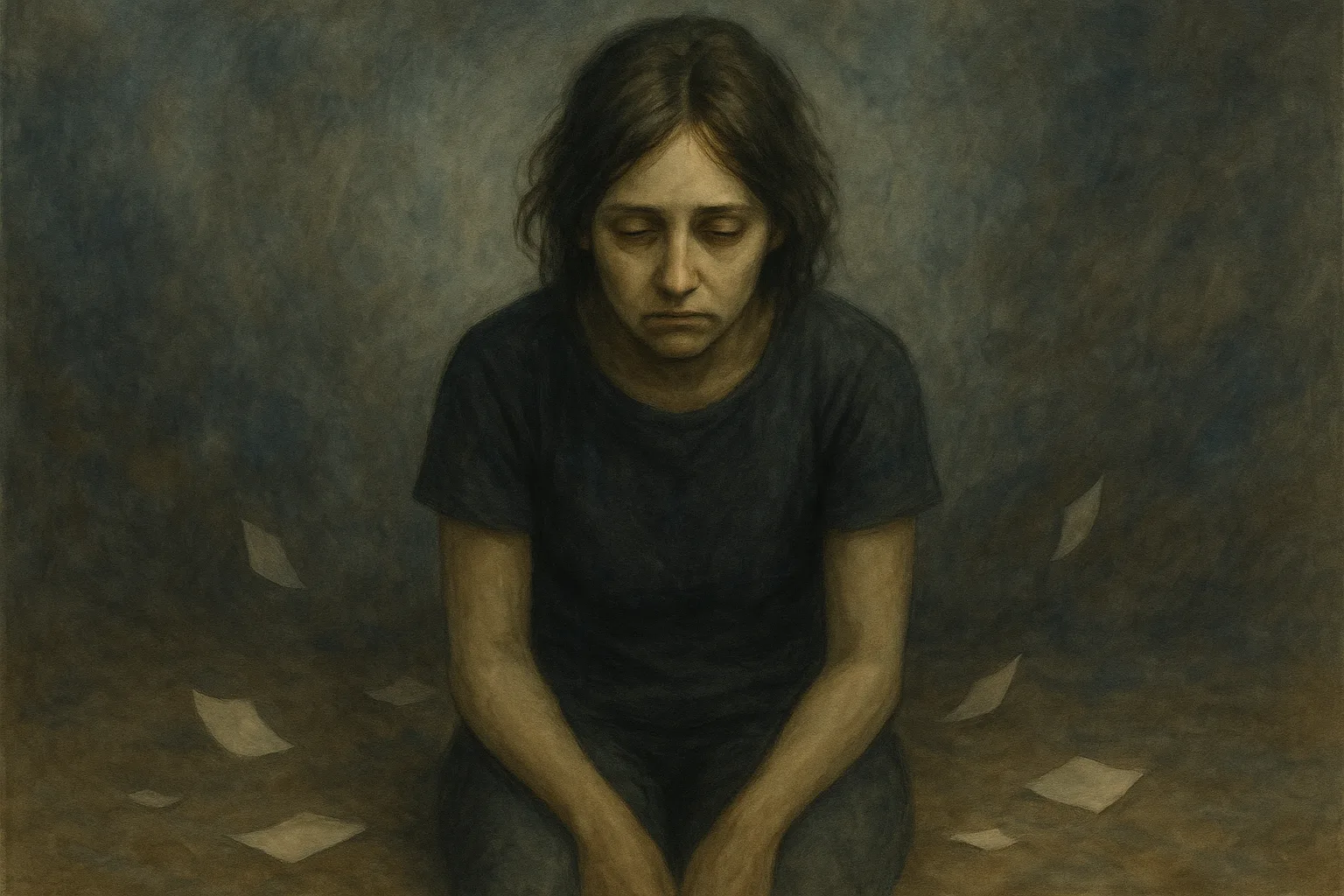

After the (hypo)manic episode or the mixed episode, depression arrives. Almost systematically. And the higher one flies, the more violent the final crash. The depressive episode is the bipolar episode that speaks most clearly even to those unfamiliar with the disorder. Literature and science have addressed it in thousands of articles. It is better known simply as depression. Between 13 and 20% of the population (according to Wikipedia) will experience it at least once in their lifetime. It is an integral part of bipolar disorder and haunts the lives of those who suffer from it.

📋 TL;DR : Bipolar depression in short

- 🕳️ Brutal crash after euphoria, sudden and severe downfall.

- 🐌 Massive slowing down: thoughts, movements, speech slowed.

- 😔 Guilt, worthlessness: self-blame, destructive shame.

- ⚫ Emotional emptiness or extreme pain, loss of pleasure (anhedonia).

- ⚠️ High suicide risk, higher than in unipolar depression.

Bipolar depression generally shares the same characteristics as unipolar depression, yet it often manifests in a more severe way according to several studies (Clark et al., 2022), and patients who suffer from it are more likely to experience suicidal thoughts than in classic depression. Its characteristics need to be clarified before addressing the danger it represents.

The DSM-5 definition

The DSM-5 (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) provides a strict definition of the diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode in bipolar disorder. Rather than paraphrasing them, I will therefore quote them:

- Depressed mood most of the day

- Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all or almost all activities most of the day (anhedonia)

- Significant weight gain or loss or decrease or increase in appetite (>5%)

- Insomnia (often sleep-maintenance insomnia) or hypersomnia

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation observed by others (not self-reported)

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide, a suicide attempt, or specific suicidal planning

The episode must include at least 5 of these criteria for a duration of at least two weeks. Among them, it must include either a depressed mood or a loss of interest and/or pleasure. With the exception of the criterion concerning suicidal thoughts and attempts, symptoms must be present nearly every day.

Bipolar depression and its specificities

The bipolar depressive episode differs from major depression in certain characteristics that are more intense and severe than its unipolar counterpart.

A brutal and sudden depression

Research suggests that bipolar depression is often more severe than unipolar depression. The explanation is simple: classic depression is rarely brutal. It develops gradually, with symptoms appearing with a delay as the episode builds in intensity. Bipolar depression, on the other hand, often follows euphoric episodes that can be extreme. Imagine all your neurotransmitters activating at the same time and being released en masse. Dopamine (the reward hormone), serotonin (the happiness hormone), cortisol (the stress hormone), and others. At some point, all your reserves are depleted. The brain no longer has the capacity to produce them quickly enough to keep up with your level of functioning.

It crashes.

This is the bipolar crash. It is often experienced in an extremely brutal way and can suddenly leave the patient in a sometimes vegetative state. It is not that the bipolar person is not making an effort. It is that they are chemically incapable of making that effort. This is the harsh reality of bipolar disorder: a chemical imbalance in the brain that can produce euphoria or melancholy. Whereas unipolar depression develops over several weeks or months, bipolar depression can activate intensely within the span of a few days. In some cases, within a few hours. This can place the person experiencing it in emotional distress.

Its atypical symptoms

Bipolar depression also often presents atypical symptoms: hypersomnia (sleeping 14 hours straight), hyperphagia (excessive increase in appetite), and very marked psychomotor slowing, according to a Swiss review (RevMed, 2017). A feeling of guilt or worthlessness that is clearly more intense is also frequently observed. Suicide risk is also higher, being up to twice as common as in unipolar depression (Healthline).

A depression without a trigger

Unipolar depression can occur without any identifiable trigger; this is even a well-documented feature of it. However, this is even more pronounced in bipolar depression. Cycles are often used to explain how bipolar depression follows hypomania/mania, but it can also occur without any trigger at all (which is even common for many affected people) and, once again, more brutally than its unipolar counterpart. A person may go to bed in a euthymic (stable) state and wake up collapsed in the morning, unable to get out of bed and massively slowed down.

Some false triggers may appear at the onset of an episode and may then seem to be the cause of the depression even though it would have occurred anyway. Bipolar people can thus be prone to seasonal depression, but that does not necessarily make it the triggering factor.

Characteristic symptoms

At the risk of repeating what can already be found in dozens of articles, I will try to bring my own voice to this list of characteristic symptoms of depression, often experienced more intensely in bipolarity.

Psychomotor slowing

This refers to being slowed down both mentally and physically. Concretely, it takes the following form (description + lived experience):

- On the psychological level:

- Difficulties thinking, slowed thoughts: all the more striking after euphoria, one is literally running in slow motion, thinking slowly

- Impoverished speech, brief answers: I speak slowly, I have no “energy” to talk (but it is not voluntary)

- Feeling of mental emptiness: it is as if nothing is happening in the neurons and nothing is felt

- On the motor level:

- Slow movements, slowed walking: whereas I usually walk so fast it looks like I am on a mission, in depression I “drag my feet,” sometimes without even realizing it

- Reduced facial movements: after spending two decades constructing my social mask (including forced facial expressions), there is suddenly nothing left—and apparently, that is frightening

- Lived experience: the sensation that my body is heavy and that getting up requires an infinite amount of energy, which I do not have

In the most extreme cases, this can lead to catatonia (complete immobility). I have never experienced it myself, but it appears to be more common in bipolar disorder than in unipolar depression.

Guilt and worthlessness

Whereas sadness predominates in unipolar depression, it is usually an extremely intense guilt, worthlessness, and sense of shame that overwhelm the bipolar depressive patient.

In bipolar disorder, guilt manifests in two ways: often irrational thoughts of having committed negative acts (believing, for example, that others are suffering because of oneself), and thoughts related to actions committed during the euphoric state that preceded the depressive state. To better understand this, one has to imagine a patient who spent several thousand euros on senseless purchases, drove dangerously, and possibly stopped their medication.

This last point is crucial. Having lived it many times, it is the main thing I reproach myself for during depression: “What if I hadn’t been stupid and hadn’t stopped my treatment? Everything is my fault.” The depressed person reproaches themselves for everything they may have done, even though they were not (fully) in control of their actions.

Devaluation is close to a feeling of worthlessness that is devastating for self-image. One starts to think that one is worth nothing, has no value as a human being, does not deserve to be loved, or worse, does not deserve to exist. Everything becomes a pretext for self-devaluation and self-denigration, for questioning one’s achievements. Our view of ourselves is entirely affected.

Emotional anesthesia

This is the sensation of feeling nothing, which strikes hard after a euphoric episode in which all emotions were overflowing and amplified. In depression, sensations are washed out (like faded colors). One has the impression of feeling a real inner emptiness, and it is a dreadful feeling one believes there is no way out of. Worse still, one thinks there is no solution.

And sometimes, the opposite happens: an extreme inner pain to the point where one could cry all the water contained in one’s body. Sometimes one cries. Sometimes one no longer even has the strength to do so. But the pain itself is very real. Many testimonies speak of endless or recurrent crying spells throughout the day, without even knowing why one is crying. We come back to it: depression has no tangible origin. It is most often the aftermath of euphoria, which leaves the bipolar patient very confused at suddenly being sad for no reason.

Cognitive disturbances

A brief word on this symptom, which shatters concentration and memory capacities and installs a kind of fog in the mind of the depressed person. They feel as if a veil lies over everything they think, feel, and see. It prevents them from functioning fully; they forget things, sometimes everything, even medical appointments that are meant to help them.

Suicidal thoughts

This is the only symptom I experience only during mixed episodes… with the exception of my first depressive episode when I was 17. Diagnostic criteria speak of suicidal thoughts and plans. They are often more present in bipolar depression than in unipolar depression, which is why depression must not be taken lightly, as it can place affected individuals at high risk, especially when depression drags on. They can set in very quickly during depressive episodes, within just a few days.

They are often seen as the only way out of symptoms that place the person in distress. To dismantle the idea of cowardice or the belief that patients do not think about their loved ones when they attempt suicide, it must be understood that this is a chemical mechanism of the brain, outside the control of the depressed person. Studies have shown a surge of egocentrism in certain regions of the brain (Erle, 2019), which makes the victim forget the consequences for their loved ones, biases their ability to reason soundly, and makes them believe it is the only solution to their problems.

The crash after euphoria

What needs to be understood is this notion of a crash—it is essential. A person can enter depression without any reason, but most often depression follows a euphoric episode. The euphoric phase involves a (massively) intense exaltation, agitation, creativity, rapid thoughts, and a feeling that everything is fine and will remain so. The (hypo)manic person’s brain is erupting; it is overactivated, running at 200 km/h. In short, they live in a kind of alternative reality where everything goes their way.

When they crash, they experience symptoms that are the opposite of all these sensations. From moving at full speed, they become slowed down—mentally and physically. They speak more slowly, walk more slowly, act more slowly, and think more slowly. The intensity of the slowing is such that it is felt and observable by those around them.

The person no longer recognizes themselves—neither in the euphoria that preceded the depression nor in the depression itself. They are flooded with constant incomprehension: from unprecedented efficiency, they are now unable to function. It is extremely destabilizing. They look at themselves in the mirror and may feel as if they are seeing someone else. Sadness takes over.

To add another layer, because they are prone to very intense guilt, they often cast a very negative, self-accusatory on their actions during the euphoric episode. Risk-taking, inappropriate social behaviors, hypersexuality, excessive spending—everything becomes material for a dark judgment of oneself.

A unique sensory experience

Many people with bipolar disorder or unipolar depression talk about it: when the episode begins, the world gradually loses its colors. The more the episode increases in intensity, the more the colors wash out, to the point of feeling as though one is seeing in black and white. Reassuringly, this is a metaphor. I specify this because for a long time (classic autistic moment) I thought it was literal and therefore did not relate to this symptom. There is, however, a grain of truth to it. Research has shown that people with depression present an alteration in the perception of contrasts and colors (Salmela et al., 2021). Shades of blue and yellow would be the most affected (linked to dopaminergic circuits), according to an article published by Time. The world therefore becomes—literally this time—more dull.

In autism, testimonies speak of various sensory manifestations of depression. Some describe heightened hypersensitivities (amplified unpleasant sensations), a loss of pleasure in pleasant sensations (partly linked to anhedonia). Others, on the contrary, describe a total desensitization to the outside world. That is what I experience. I am neither sensorially satisfied by music in my ears, nor fascinated by traffic lights or nighttime lights, nor even assaulted by external stimuli…

With the exception of tactile sensations, which become intensified. Touching myself becomes a challenge, as I react abruptly to the slightest contact—unless it comes from a few people with whom I am already comfortable when I am stable. Food completely loses its flavor (when I have enough energy to eat). I cannot judge smells, as I was hyposensitive to smell for 28 years and my last depression dates back to that period. My vision is also affected; I am less sensitive to light, as if it too were dull, much like the colors I perceive.

As a small anecdote, I once personified my sensory sensitivities by calling them themselves “depressive,” because they no longer responded to anything—like me, no longer responding to positive things.

My atypical case thus serves as a reminder that there are as many different manifestations of autism as there are autistic people.

Many autistic people also stim less during depressive episodes. Depression can make stimming less accessible or less automatic, which leaves the autistic person “at risk” when faced with sensory stimuli they can no longer regulate, giving the sensation that their sensory hypersensitivities are amplified.

Anhedonia

This is the symptom I mentioned earlier. It refers to the loss of interest or pleasure in activities that are normally enjoyable. The depressed person no longer takes pleasure in anything or almost anything. The more the episode intensifies, the more striking the symptom becomes, to the point where the person can become totally apathetic and no longer smile at the slightest happy event or at things they usually enjoy. It is the main symptom of depression—alongside depressed mood.

In autistic people, anhedonia can take a more radical, more mutilating form. Stims, routines, rituals, and special interests are often the main source of pleasure for autistic people. When they are affected by depression, it is as if a part of themselves were taken away. I talked about this in my article on stimming: it is a part of oneself for the autistic person. When it is lost, it is like a disconnection from oneself. Even special interests no longer bring joy, even though they may occupy the autistic person’s mind throughout the day. It is not simply a loss of pleasure in a passion; it is the loss of pleasure in one’s identity.

In this state, I sometimes scared myself by no longer feeling the slightest hint of joy at the idea of engaging in my special interests. This is dramatic when one knows that, in a stable state, I would happily infodump to anyone about one of my favorite topics. The episode was so intense that I did nothing at all. I sat cross-legged in front of my television, tears not flowing because I was too drained of energy, trying to start a movie without feeling the slightest excitement at the idea of immersing myself in it. The very idea of watching a film felt more exhausting and tedious than soothing. So I did nothing.

📋 TL;DR : Keep in mind

- Bipolar depression is not simple sadness: it is a brutal collapse, often following a euphoric phase.

- It manifests as massive slowing (thoughts, movements, speech), intense guilt, and destructive worthlessness.

- Emotional anesthesia and anhedonia create an inner void, cutting one off from pleasure and sometimes from one’s identity.

- Suicide risk is high, reinforced by the severity of symptoms and the speed of the crash.

- In my case, autism modulates sensory perceptions and amplifies the impact of anhedonia, making the episode even more devastating.

After the incandescence of mania, depression is seeing a world in black and white. You don’t choose it—you endure it.