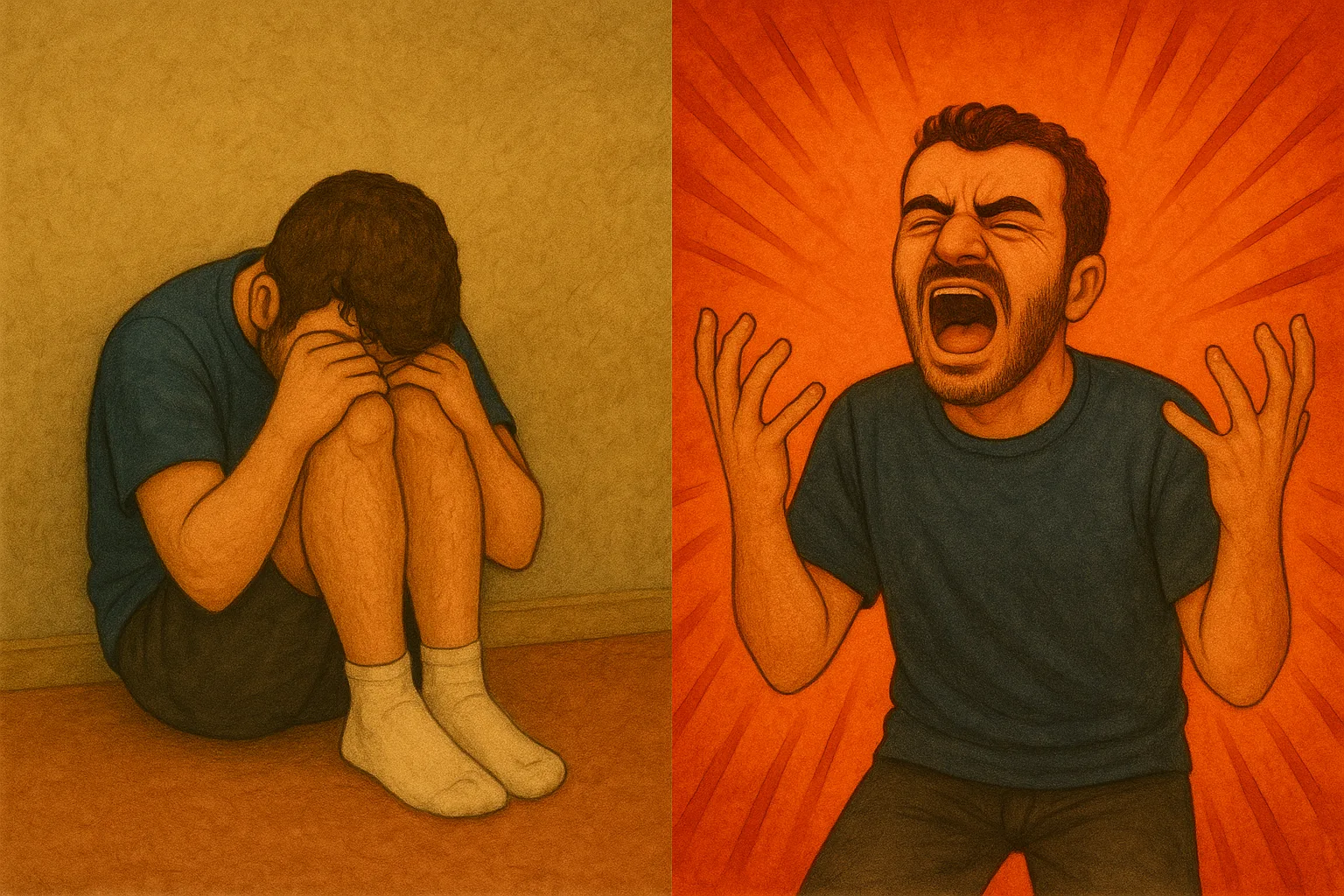

In the collective imagination, an autistic person is someone withdrawn, exceptional at math, calm, and rocking back and forth. What many people don’t realize is that autistic individuals can also experience intense emotional outbursts (meltdowns) and internal shutdowns (shutdowns). These crises have various causes, but sensory overload is the most common trigger.

📋 TL;DR : Autistic crises in short

- Shutdown = implosion (mutism, withdrawal, stillness).

- Meltdown = explosion (screaming, crying, agitation).

- These are not tantrums, but neurological responses to overload.

- During: reduce stimuli, offer calm or quiet presence.

- After: rest, support, zero blame.

- To learn more: [Shutdown] / [Meltdown]

It is often mentioned in many articles that these autistic crises are not exclusive to autistic people, and that allistic individuals may also experience similar responses under extreme stress. This is why it’s important not to confuse burnout-related collapses or panic attacks with autistic crises.

Neurological explanation

Due to increased brain hyperconnectivity (Achuthan et al., 2023 and Limon & Corona-Moreno, 2025), stimuli are amplified instead of being filtered. Every detail comes through without prioritization. The amygdala also activates more strongly (it’s the center of fear and emotional processing), which raises stress levels. Eventually, the prefrontal cortex — responsible for planning, self-regulation, and cognitive control — reaches saturation. That’s the overload point; it crashes. The resulting response, specific to autism, is shutdown or meltdown.

These crises are neurological and specific to the autistic brain structure. In allistic people, we may observe stress-induced collapses or panic attacks. Shutdowns and meltdowns are specific to autistic neurology: they are not equivalents, even if they may appear similar from the outside.

Definitions of autistic crises

There are two main types of autistic crises. In a study conducted by the University of Cambridge focused on these responses, among a cohort of 504 participants, 401 reported experiencing shutdowns (80%) and 358 reported meltdowns (71%). While not universal, they are therefore highly common within the autistic community.

Shutdown

A shutdown, the autistic withdrawal, is a response similar to the freeze reaction. It manifests as motor inhibition (slowed or halted movement), partial or total mutism, and social withdrawal. The person may appear unresponsive to stimuli, struggle to communicate — or stop communicating altogether — and may seek isolation.

As highlighted in a qualitative study (Phung et al., 2021) based on narratives from autistic children, shutdowns are sensory, emotional, cognitive, and even physical collapses. This explains why after a shutdown, autistic individuals feel entirely depleted of vital energy.

Meltdown

A meltdown, the emotional explosion, is more akin to fight/flight. It involves extreme activation of the sympathetic nervous system (adrenaline release, motor agitation, abrupt movements). More concretely, instead of social withdrawal, it manifests as overwhelming emotional overflow. Everything activates. The experience is chaotic and extremely intense. Unlike a panic attack, the person isn’t seeking relief — they simply need the sensory or emotional pain to stop.

A study (Soden et al., 2025) suggests intra-insular hypoconnectivity in the insular cortex (a key region for integrating bodily, emotional, and sensory information). This could lead to chronic hypervigilance and excessive reactivity, even to stimuli considered neutral.

I will discuss in their respective articles how each of these crises manifests, along with my personal experience.

The origins of these crises

For both, the causes are varied, but there is always one underlying mechanism: overload — whether:

- Sensory: too much noise, light, movement, smell, touch, or even taste

- Emotional: intense anxiety, frustration, or even strong positive emotions in some cases

- Cognitive: unpredictability, cumulative effort to understand, adapt, or mask, too much information

- Social: interactions that are too long or intense, conflict

The issue is that overload isn’t always obvious before it happens. An autistic person may accumulate multiple sources of overwhelming stimuli without realizing they’re heading toward a crisis. And even when they do notice it, it may already be too late — or impossible to leave the situation. The first shutdown I consciously identified happened after my best friend deconstructed everything I thought I understood about environmental issues.

Too much information to integrate in too little time + major shifts in perspective → shutdown.

Delaying crises

My solution when I sense a crisis coming is to go home in hopes of short-circuiting it, or at least delaying it long enough for it to happen safely. Autistic crises can appear suddenly after overload, but they can also be delayed, occurring only once the autistic person is alone somewhere they perceive as safe. I can sometimes delay a shutdown for a while, but doing so will only make it stronger if I don’t remove myself from risky stimuli. Delaying a meltdown is almost impossible for me. The internal pressure is so intense that I can explode without warning.

Generally, when an autistic person (myself included) is nearing a crisis, they may communicate less, seek shelter from sensory input, stim more intensely, and become exhausted.

It’s important to note that not all autistic people experience these crises — and some may only experience one type, not both.

Warning signs

As mentioned, shutdowns and meltdowns are often preceded by various early indicators. It’s common to observe the person withdrawing (or trying to withdraw), with increased sensory hypersensitivity. They may communicate less or struggle to express themselves. They may begin stimming more intensely in an attempt to regulate the overload. They may appear exhausted and/or irritable and restless. From the outside, they may look tired, grumpy, or as if they’re “glitching.” This is the point where support and intervention are most effective.

Management strategies

The autistic person is often unable to fully function during this time, so the people around them can help by reducing the load and supporting them through the crisis.

🌋🧊 During the crisis

Once the crisis has started, it’s possible to help an autistic person experiencing a shutdown or meltdown through simple actions: ensuring a calm environment, offering their sensory tools if they have any, asking whether they accept physical contact and, if so, providing deep pressure (some autistic people find strong physical pressure soothing during the crisis — that’s my case — such as being held tightly in someone’s arms). The most important thing is to let them isolate themselves if they need to — or to stay present if they ask for it (and can tolerate it).

🛌 After the crisis

It’s worth repeating: whether it’s a shutdown or a meltdown, autistic crises leave the person exhausted. They need time to rest, especially if they must maintain some level of academic or professional functioning. If possible, offer help with daily tasks (meals, cleaning). Most importantly: do not blame them. The crisis is neurological, automatic, and outside of their control.

🛡️ Prevention

Preventing crises isn’t always easy. However, it’s important to respect the autistic person’s needs as much as possible: avoid highly stimulating environments, plan breaks so they can recharge, and avoid interfering with their routines and rituals. Life will always contain unpredictability — but reducing it helps provide as much stability as possible. If this seems restrictive, it’s because these needs come from neurological functioning, not preference.

When the brain multiplies crises

Several mechanisms contribute to this phenomenon: after a shutdown or meltdown, the brain becomes more likely to trigger additional crises in the days or weeks that follow. The primary reason is the drastic reduction of tolerance to stimuli caused by the crisis, which increases the risk of recurrence. One study showed reduced amygdala habituation to repetitive stimuli in autistic individuals. The findings suggest difficulties filtering sensory input and desensitizing over time (Webb et al., 2017).

The brain also retains a memory of crises. It records them similarly to how it records trauma. The amygdala may become emotionally hypersensitive (UCDavis Health), reacting more quickly, which can lead to additional crises being triggered faster and by less intense stimulation.

Finally, crises do not resolve the root problem — they only stop the overload they produce. If the underlying issue is not addressed afterward, it may lead to further crises. I have experienced multiple crises in a single day. The first was emotional and social:

Misunderstanding hypocritical behavior

→ Frustration

→ Meltdown

→ Heightened sensory sensitivities

→ Shutdown

→ Emotional issue unresolved + new trigger

→ Meltdown(One single day)

The need for understanding

I emphasize that these crises are not voluntary, and that understanding and kindness are essential when witnessing a shutdown or meltdown. It’s also important to remember that we are not always able to detect overload early enough to prevent a crisis. And if it impacts you in some way, remember that the autistic person is the one impacted first and most intensely. They are the first victim of the situation. My experience is only one example — every autistic person lives their crises differently.

The difference with a panic attack

Often referred to as an “anxiety attack.” I mention it because before I was diagnosed, I used this term to describe my autistic crises — it was the closest reference I had. Yet they are very different realities. The symptoms of panic attacks are clearly defined in the DSM-5 (the diagnostic manual for mental disorders).

- Triggers:

- Autistic crises: sensory/emotional/social/cognitive overload

- Panic attacks: fear and intense stress, anticipation of danger

- Internal experience:

- Autistic crises: need to withdraw or escape, pain from stimuli, internal chaos

- Panic attacks: fear of dying, suffocating, losing control, sense of imminent danger

- Expression:

- Shutdowns: withdrawal, mutism, stillness

- Meltdowns: agitation, crying, yelling

- Panic attacks: heart palpitations, shaking, hyperventilation, chest tightness, ongoing alertness

- Duration:

- Autistic crises: sudden, from a few minutes to several hours depending on intensity

- Panic attacks: build up, peak around 10–20 minutes, then gradually decrease

- After the crisis:

- Autistic crises: extreme exhaustion, need to isolate, to stim

- Panic attacks: relief but fear that it may happen again

My crises manifested as amplified sensitivities overwhelming my brain. I would flee the environment, sit down, cry intensely, rock back and forth, hit the walls, and wait for it to pass. I called them panic attacks because I was afraid of appearing strange. In reality, they were meltdowns.

Some common misconceptions

“Meltdown = a tantrum or intentional anger”

Reality: A meltdown is a neurological response caused by overload affecting the autistic person. It’s a sign that they’ve reached their limit, and they have no control over it.

“Shutdown = voluntary silence or just tiredness”

Reality: It is also a neurological mechanism that inhibits (blocks) certain functions such as speech, which is extremely energy-demanding.

“Only children have crises”

Reality: Children are more prone to meltdowns because they have fewer regulation strategies (shutdowns also exist in children). Adults are more prone to shutdowns because they are more “socially acceptable,” but they also experience meltdowns.

“There is only one type of crisis”

Reality: “There are as many forms of autism as autistic people.” Following the same logic: “there are as many expressions of crises as there are autistic individuals.”

“It’s just a panic attack.”

Reality: Similarities exist, but panic attacks = anxiety. Autistic crises = sensory/emotional/cognitive overload.

“The crisis is relieving.”

Reality: Since the person externalizes during a meltdown, it may seem like they’re releasing something. In reality, the crisis drains them of all energy.

“It’s enough to force, touch, or shake them to snap them out of it.”

Reality: This can worsen the crisis by increasing sensory overload. Never touch the person unless they accept it or ask for it.

“They should have anticipated the signs to avoid affecting others.”

Reality: The signs are not always identifiable or manageable. They are not constant — they vary.

📋 TL;DR : Keep in mind

- Definitions:

- Shutdown = implosion (mutism, withdrawal, stillness).

- Meltdown = explosion (screaming, crying, agitation).

- Cause: sensory, emotional, cognitive, or social overload.

- Difference from panic attack: trigger (overload vs fear), duration (sudden vs gradual), after-crisis (extreme fatigue vs relief).

- Warning signs: withdrawal, reduced communication, heightened sensitivities, increased stimming.

- Management: reduce stimuli, respect the need for isolation or presence, rest and support after the crisis.

- Prevention: breaks, respecting routines, limiting unpredictability and overload.

📚 To dig deeper

Explore Autism hub, which brings together all my resources on autistic crises, sensory overload, routines, and autistic functioning.

Originally published in French on: 26 Oct 2025 — translated to English on: 20 Nov 2025.